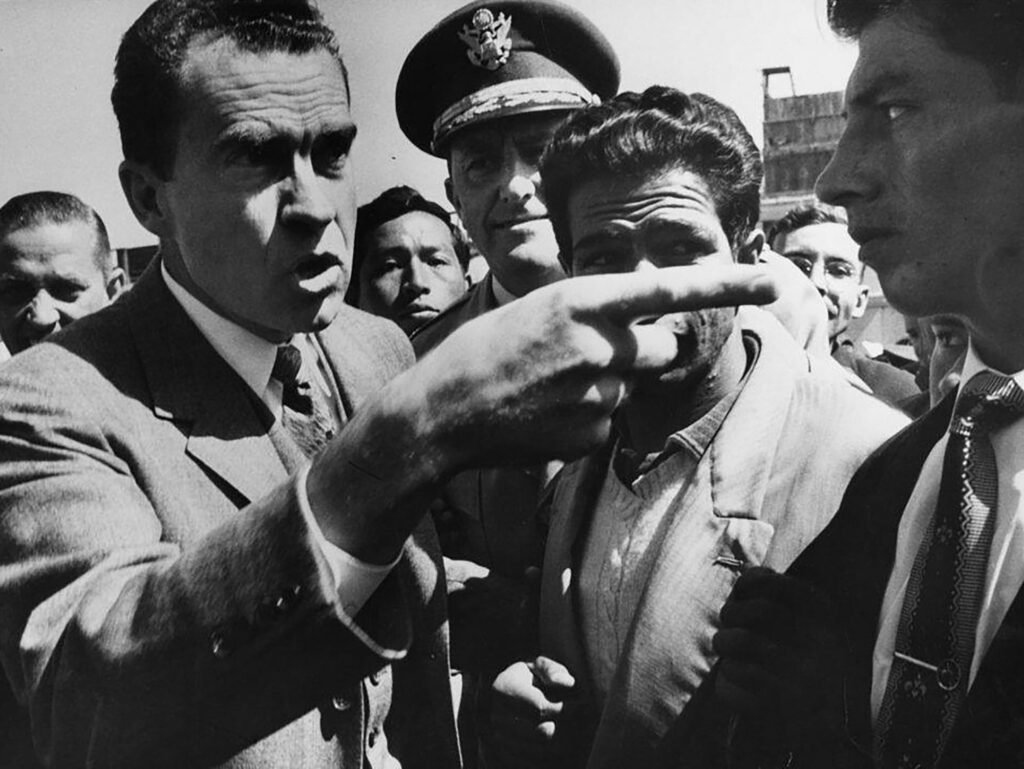

Nixon’s “good will” tour of Latin America in the fall of 1958 was described by the eminent American journalist Walter Lippmann as a “diplomatic Pearl Harbor”. Oblivious to the resentment that had been building over post-war U.S. policy in the region, State Department officials had instructed embassy personnel in each of the eight nations he would visit to arrange meetings with “local citizens in reasonably large numbers” and to make sure to include labor representatives, “farm groups” and communicated the vice president’s desire to “to meet man in street”.

An official retinue of three, that included the president of the Export-Import Bank, and twenty reporters made their first stop in the Uruguayan capital, where U.S. restrictions on trade had opened the door to financial overtures by the Soviets. A visit to the University of Montevideo resulted in the arrest of several students carrying signs that read “Fuera Nixon” (Out Nixon), “Wall Street Agents” and “Little Rock”, alluding to the ongoing issue of school segregation in the United States.

Argentina was next on the itinerary. During a Q&A with university students, Nixon contested the notion that the overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala by the CIA and United Fruit four years earlier constituted U.S. intervention and stated that “dictatorships were repugnant to [Americans]” before leaving to conduct his one-day visit with Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner amid boos and cries of “Argentina is not for sale”.

After promising to increase loans for the Stroessner regime, the vice president landed in La Paz, Bolivia to confetti and pamphlets denouncing his visit. Although access to Bolivian mineral resources had been a top priority for the Eisenhower administration, the United States’ own limited quotas for copper, zinc and lead, coupled with surplus sales of Soviet tin was resulting in serious trouble for the Bolivian government, which increasingly relied on the military to repress labor movements in its mining sector.

Nixon shrugged his shoulders and moved on to Peru, where the naïveté of State Department officials would be put on full display. Disregarding clear indications that he wouldn’t be well-received, Nixon’s advisors encouraged him to accept an invitation to speak at San Marcos University, the country’s most prestigious institution of higher learning. Nixon himself was quite aware of the danger and tried, privately, to save face by persuading the rector to rescind the invitation, but to no avail.

Upon arrival, hundreds of students prevented his entourage from even crossing the gates of the university, throwing rocks, bean bags and tomatoes at the Americans. Nixon’s aide, Jack Sherwood, was struck in the face and suffered a chipped tooth, while a defiant vice president scurried back to the motorcade and hopped on the trunk of the black convertible. “You are cowards”, he shouted at the students with a raised fist before his security detail evacuated him from the scene.

Humiliation in Lima was followed by the picture of civility in Quito, Ecuador, where the Ecuadorian president made sure to avoid any ugly scenes. A short respite before heading off to Bogotá and meeting with the newly-elected president, Alberto Lleras Camargo, who came to power as part of a coalition government that marked the end of Colombia’s civil war and the beginning of a period of conciliation.

Lleras Camargo was a liberal politician with an unimpeachable record of pro-U.S. positions. In 1948, on the eve of the bloody conflict known as La Violencia, Lleras Camargo was elected as the first Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), the reconstituted body of the International Union of American Republics, later known as the Pan-American Union and the primary vehicle to achieve the goals of the Monroe doctrine in Latin America.

Nixon need not worry about Colombia, which already had close ties to the U.S. military establishment unlike neighboring Venezuela, where the eventful tour was set to conclude. Fully cognizant that a nationalist party had just re-taken the reigns of government from a U.S.-backed military dictatorship, the vice president’s team took no chances and scheduled all meetings to take place at the U.S. embassy in Caracas.

Venezuela’s new government was poised to curb the corporate looting of the country’s most valuable natural resource through a new tax regime, inspiring other oil-rich nations around the world to follow suit. This was especially problematic because of the dominant presence of Standard Oil in the country, which extracted more than 50% of its crude from Venezuela at a time when the South American oil fields accounted for the largest crude output in the world, by far.

Pat Nixon’s red dress was ruined by tobacco juice and other garbage that rained down on the vice presidential couple before the twelve secret service agents could whisk them out of Simon Bolivar International Airport. It was immediately apparent that planning an official visit to Venezuela while harboring its recently-deposed dictator and his blood-thirsty chief of secret police in the United States had been a terrible mistake.

Matters only got worse as Nixon’s caravan tried to make its way down the streets of Caracas with mobs of angry Venezuelans trying to storm his motorcade and hostile vehicles darting in front of them. Panic began to set in at the White House as “Operation Poor Richard” was activated by Eisenhower and hundreds of troops were deployed to Guantanamo and Puerto Rico in case an invasion of Venezuela became necessary to rescue his second-in-command.

Not even an escort of military tanks could dissuade Venezuelans from sending a message to Washington, which Nixon delivered to Allen Dulles personally upon his return, deciding to forgo formal debriefings and speak with the CIA boss directly. The soft power approach in Latin America inherited from FDR’s Good Neighbor Policy had reached its limits and a different strategy had to be employed in order to meet the challenges posed to American interests by Venezuelan self-determination and the proliferation of class consciousness along Colombia’s fertile crescent and other parts of Latin America.

—

Colombia’s peasantry, by now radicalized after years of bloody resistance and deemed “terrorists” by Lleras Camargo, were placed under the microscope of American intelligence agencies and the U.S. Defense Department. Less than a year after Nixon’s tour, veterans of the CIA’s counter-guerrilla operations against the Hukbalahap (HUK) rebels in the Philippines arrived in Colombia to study the uprisings and prepare a report for President Eisenhower.

Leading the survey team or Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), was a Danish-American CIA officer named Hans Tofte with ample experience in guerrilla warfare throughout Asia. Officially handled through the State Department, the team’s affiliation to US intelligence was never disclosed to the Colombian government.

Working alongside Tofte in Colombia would be individuals such as Col. Napoleon Valeriano, a former chief of police in Manila, who had collaborated with the notorious Edward G. Landsdale to crush the HUK rebellion and an aid to the late Philippine president Magsaysay. Other members of the six-man team included Army Lt. Col. Koontz, an infantry officer attached to the MAAG group due to his previous experience during a four-year US Army Mission in Colombia. Koontz had helped establish the Escuela de Lanceros in Usaquén, an unconventional warfare training facility for the Pinilla regime modeled on the US Army Ranger School, which was under consideration as a possible base for counterinsurgency training.

After two months, Tofte’s team delivered an initial briefing to Colombian and American officials in Bogotá before heading to Panama to brief CINCARIB (Commander in Chief, Caribbean). Major Charles T. R. Bohannan, another member of the special MAAG crew, remained in Colombia a few more weeks to shore up loose ends and follow-up on plans to establish a public affairs section for the Colombian military.

Before leaving, Bohannan was given a final mission. A secret meeting was to be arranged through Lleras’ aid-de-camp with either Leopoldo García, a.k.a. General Peligro, or Jesús María Oviedo, a.k.a. Mariachi, two of the top guerrilla leaders in southern Tolima. In his directive, Tofte made clear his preference for the latter “for various reasons incl. time-saving [sic.]”.

Not long after Bohannan’s return to the United States, Jesús María Oviedo (Mariachi) would assassinate fellow guerrilla leader Jacobo Prias Alape, a.k.a. Charro Negro over a cache of stolen weapons, and cause a major rift among Tolima’s rebel groups. General Peligro, his former ally, then moved to destroy Oviedo’s power base with the help of the Colombian army.

Charro Negro’s murder would prove to have serious unintended consequences for Colombia and the United States’ fledgling counterinsurgency efforts in Tolima and surrounding countryside. Prias Alape’s orphaned guerrilla forces would come under the command of an ambitious Marxist rebel formed in the bloodiest days of La Violencia by the name of Manuel Marulanda Vélez, a.k.a. Tiro Fijo (Sure-Shot).

Vélez went on to mount an effective resistance against the increasing incursions into rebel strongholds by the US-assisted Colombian military over the coming years. Determined to use ‘southern Tolima as the staging ground for a nation-wide revolution’, Sure-Shot founded the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) guerrilla army in the mountains of central Colombia and became a thorn on the side of America’s best laid plans for the next four decades.

A month after Tofte’s team completed its preliminary majority report on the Colombian situation, Lt. Col. Koontz submitted a minority report on behalf of the DoD to the State Department delineating his alternatives to the recommendations made in the CIA’s version. Koontz correctly challenged the idea that communism was at the root of Colombia’s violence and advised against using covert methods to beef up the country’s internal security apparatus.

“The questionable future gain from penetrating the organizations of a very friendly power”, Koontz warned, “should be weighed against the real danger of damaging relations”. In addition, he insisted that any military training programs for the Colombian Armed Forces be handled by the DoD and not the CIA.

A second preliminary majority report prepared in co-ordination with interagency stakeholders was delivered to Colombian president Lleras Camargo in March. That document was denounced as “doctored” and “watered down” by Tofte and other team members partial to the CIA’s approach, who communicated their misgivings to Lleras privately.

Lleras Camargo went to Washington to plead with Eisenhower. During an extensive state visit the following April, the former Secretary of the Organization of American States (OAS) complained about the noncommittal nature of the report. Ostensibly unaware that he was pushing the CIA’s agenda, he pressed the American leader to help him “liquidate the guerrilla problem”, as the State Department put it, and implement the six-point program put forward by Tofte’s team.

These included recruiting Lancero school graduates to create a special counter-guerilla combat force within the Colombian military, and the establishment of a department of propaganda with “covert psychological warfare capability”. At Camp David, the two heads of state agreed to make counterinsurgency the top priority of the US mission in Colombia and move forward with economic assistance programs to bolster imports of Colombian goods.

Secretary of State Christian Herter received the team’s final report the following May, elaborating on the findings of the preliminary majority report and adding Lleras Camargo’s latest input. The comprehensive review oscillated between a basic misunderstanding of the factors driving the radicalization of Colombia’s peasantry and a sober analysis of the monumental obstacles standing in the way of any long term solutions.

Peppered with phrases like “economic terrorism” to describe grassroots campesino movements and “genocide or bankruptcy” to characterize the urgency of the threat to Lleras Camargo’s coalition government (National Front), the report promoted a strategy of pacification and grossly miscalculated the time it would take to eliminate the guerrillas, suggesting they could be subdued within 10 to 12 months. Nevertheless, concrete action was delayed by ongoing interagency rivalries, differences of opinion and the competing priorities of the American security establishment.

—

Months after Nixon’s return from South America, the CIA had dispatched Lyman Kirkpatrick to Havana, Cuba. The agency’s Inspector General was tasked with evaluating U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista’s internal security apparatus and the status of the rebel situation in the mountains following a failed attempt to establish direct contact with Fidel Castro’s inner circle.

Cuban elites, well aware that the rebel forces of the wealthy sugar planter’s son were on the verge of victory, told Kirkpatrick to start severing ties with the dictator as soon as possible and ignore American ambassador Earl Smith, who still believed that a few more arms shipments and counterinsurgency advisors could reverse the tide.

Cuba’s economic stability had been severely compromised by a revision to the 1948 Sugar Act in 1956, intended to mollify American sugar farmers who had mounted a national grassroots campaign to increase their own sugar quotas. Although U.S. interests controlled approximately 40% of Cuba’s sugar industry, its relative importance was minimal. Whereas the 60% or so that remained in Cuban hands represented the island’s core export and a central pillar of its economy.

In place since the 1930s, sugar quotas were part of a market control mechanism implemented by the United States to monitor the stock price and production of this critical commodity across eight “supplier regions” that included domestic and foreign producers in the Caribbean. This system was codified in 1948 and periodically revised by Congress to meet changing circumstances. The 1956 revision, in particular, greatly reduced Cuban sugar quotas and seriously harmed the island which depended on the United States to absorb more than 50% of its production.

There has never been a more critical time to support independent media

RDMPRESS relies on your support to produce independent journalistic content. Please consider making a donation today.

Left to fend for itself in the much more volatile non-U.S. markets, Batista’s grip on power could not survive the economic and social pressure caused by plummeting sugar prices. And as would happen again and again over the following decades in different parts of Latin America, issues that arose from regional political and economic realities were superimposed onto largely fictional Cold War narratives to deflect and justify broader hegemonic goals.

Kirkpatrick turned to a newspaper man the agency had recruited in 1950 by the name of David Atlee Phillips, who ran a PR firm in Havana as a cover. A veteran of the CIA’s operation in Guatemala in ’54, Phillips gave the Inspector General a concise overview of the reality: The economy was in shambles and it was just a matter of time before the revolutionaries came down from the Sierra Maestra and walked straight into the capital.

At their meeting in a Berlitz language school, Phillips suggested the creation of a third political force that would serve American interests and provide a way for the United States to begin distancing itself from the regime they had propped up since 1952. A psychological warfare specialist, Phillips suggested conforming a group of men that would represent a triumphant return of the government deposed in the U.S.-backed 1952 coup. Kirkpatrick liked that idea very much, but worried that Washington would not go along with it.

Opposition to Phillip’s plan was strongest from the CIA’s long-time Western Hemisphere Division chief, J.C. King, who believed that the only way to govern in Latin America was through military dictatorships and strongmen. The agency’s Directorate of Intelligence, on the other hand, sided with Phillip’s solution, causing a rift inside the CIA about what to do regarding Cuba’s rapidly deteriorating situation. For the next several months, the CIA vacillated on which direction to go and considered several options, including supporting Fidel Castro or one of the other guerrilla fronts that had emerged over the last few years.

By new year’s eve 1958, it was all over. Fidel Castro defeated Batista’s crack units in Santiago de Cuba and began his inexorable march towards Havana. The dictator and his cabinet were given asylum in neighboring Dominican Republic, where another U.S.-backed strongman, Rafael Trujillo, started organizing a “foreign legion” of mercenaries to stop the idea of a people’s revolution from spreading any further. Aided by the CIA, Trujillo put together a band of soldiers-for-hire, including agency infiltrators and hundreds of Batista’s former troops for an abortive invasion of its Caribbean neighbor.

Within months, mercenary pilots were dropping bombs on Havana and setting fire to the sugar cane fields recently expropriated by Cuba from the United Fruit Company. U.S. Secretary of State and long-time legal counsel for the famous banana concern, John Foster Dulles, rejected Castro’s bid to negotiate a truce, and pressured European banks into canceling a $100 million-dollar loan to the fledging Caribbean government.

No declaration of war or official policy statement had been issued by the U.S. government, as unmarked planes with incendiary payloads kept taking off from Guantanamo Bay’s Naval airfield to terrorize Cubans into submission. Shell, Standard Oil, and Texaco, which owned 100 percent of Cuba’s refineries, refused to process any crude sourced from the Soviet Union, and Belgium’s arms shipment to Cuba was blown to smithereens in Havana harbor, killing 50 people.

Hitting every possible pressure point, the CIA began recruiting members of the Chicago outfit and the New York crime families to put a contract out on Fidel Castro, counting on the mobsters’ motivation to recover the lucrative rackets they’d been running in Havana until the revolution smoked them out. By summertime, Miami had become the de facto headquarters of the agency’s regime change operations, working closely with members of the Cuban oligarchy and former political elites now exiled in the city, and trying to build a counter-revolutionary movement.

—

Cuban refugees started arriving in Miami by the thousands in 1961. Many were flown in directly, with their entire families aboard commercial airliners. Others came on small boats and a few were rescued in the open sea from makeshift rafts. By the end of the year almost 50,000 had reached U.S. shores, instantly doubling the number of Cubans already living in the United States. The fire-bombing of Cuba’s sugar cane fields continued as maximum economic pain was inflicted on the island. Eisenhower cancelled Cuba’s sugar quota and ordered his CIA director and one-time president of United Fruit, Allen Dulles, to come up with a plan for regime change.

Meanwhile, Colombian president Lleras Camargo, fresh from his 13-day visit to Washington D.C. stopped by Miami on his way back to Bogotá, where his newly-appointed Consul, Felix J. Lievano, was poised to lead the diplomatic mission in line with Eisenhower’s desire to use Colombia as “showpiece” for the projection of US power in Latin America.

On hand for the official welcome at Miami International Airport were the Mayors of Miami and Miami Beach, County Commissioners and other local officials. The Colombian head of state kicked off the last 24 hours of his two-week itinerary at a reception sponsored by Standard Oil subsidiary ESSO (Petroleum International Co.) at the University of Miami’s Lowe Art Gallery, surrounded by priceless pre-Columbian artifacts and works of art shipped from South America on ESSO’s private transport planes. Lleras made sure to acknowledge his friendship with ESSO’s majority shareholder and then-governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, in his prepared remarks.

“I doubt one can find two people born in such different countries and circumstances, who could have discussed the political problems in which they have both been involved in, with more sincerity and agreement between points of view”, Lleras boasted as Standard Oil President John Kenneth Jamieson listened in the audience before rising to receive the Grand Cross of the Order of Bocaya – Colombia’s highest commendation and typically reserved for military officers or heads of state. On this occasion, the award was presented “for outstanding achievements in service of Colombian culture”.

This seemingly innocuous celebration of Colombian art was part and parcel of Eisenhower’s government-sponsored psychological warfare initiatives, laundered through the private sector and acts of so-called ‘cultural diplomacy’ for the express purpose of mitigating negative responses to U.S. foreign policy and convincing the ‘free world’ that “[America’s] military counter-measures were a matter of immediate urgency”, as delineated in a 1955 review of U.S. propaganda operations.

Eisenhower believed that there would “never be enough diplomatic information officers at work in the world to get the job done”, as he wrote in a letter to noted feminist and CIA asset Anna Lord Strauss. He was adamant that in order to win the Cold War “thousands of independent private groups and institutions and of millions of individuals” had to be recruited to promote the American way of life around the world.

To this end, Eisenhower created the People-to-People program. An ambitious public-private endeavor intended to engage civil society and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in his quest to “take immediate and vigorous action to demonstrate the superiority of the products and cultural values of our system of free enterprise” and ultimately, to foster a favorable atmosphere abroad for U.S. policies through the selective use of culture.

As Consul General, Felix Lievano spearheaded Eisenhower’s People-to-People projects in Miami and Colombia, en route to a much broader level of integration and American tutelage in anticipation of Miami’s burgeoning role as a critical port of entry for South American goods and a budding counterinsurgency partner for the national security state. Particularly important for Lievano, who would soon return to Colombia and assume the directorship of national customs police, supervising the movement of all licit and illicit cargo.

In the meantime, Lievano set the tone for a new era of US-Colombia collaboration on matters of internal security camouflaged as cultural exchange during his short tenure at the helm of the Colombian consulate in South Florida. Lleras Camargo’s visit helped to raise his profile in the community, especially after the special Organization of American Sates (OAS) luncheon held in the President’s honor at the brand new Dupont Plaza Hotel in downtown Miami.

An enormous seal of the OAS hung on the wall directly behind the dais, where Mexican Ambassador Vicente Sanchez Gavito and other foreign diplomats from Latin America flanked the former Secretary General. Listening to Dr. Lleras Camargo among the 400 distinguished guests in the banquet hall was none other than Allen Dulles’ hand-picked Asst. Secretary of State for Inter-American affairs, Roy R. Rubottom Jr., who had orchestrated Nixon’s disastrous “good will” tour of South America.

The “Nixon incidents”, as they would be referred to in later CIA communications had sparked serious debate on Capitol Hill about the direction of U.S. foreign policy in the region and moved U.S. lawmakers to openly question the administration’s approach. Eisenhower had responded by forming the Draper Committee, a nine-member panel put together for the ostensible purpose of conducting an “objective” review of U.S. military assistance programs, comprised of three retired generals, a navy admiral and a former assistant secretary of defense.

Dulles made sure the committee’s final report would leave military assistance programs “on a sound long-term basis” and Rubottom went to bat for the administration during a Senate hearing by stressing the “crucial” need for continuing to establish military links with Latin American nations as a source of indirect “capital for socioeconomic development”. In other words, Rubottom posited that Latin American countries could devote more of their resources to promote economic growth by turning over internal security matters to the U.S. military and ensuring American hegemony across the Western Hemisphere.

Rather than cutting back on military assistance programs, the Nixon incidents had resulted in their expansion and a doubling down on the use of covert operations to facilitate U.S. primacy on the continent. Just a few weeks before Lleras Camargo boarded his private jet back to Bogotá, Allen Dulles explained to President Eisenhower how a paramilitary force of Cuban exiles could be trained in a matter of six to eight months and that $100,000 had already been raised through private “US sources” to start work on the necessary logistics. Dulles’ plan to overthrow the revolutionary government of Fidel Castro would end up costing close to $5 million.

Later that year, the American people elected a young Senator from Massachusetts as their new president. John F. Kennedy would continue most of his predecessor’s policies, including the promises made to Lleras Camargo earlier that spring, with the largest military aid package to that point in U.S. history as part of the first securitization agreement between the US and a Latin American country. The so-called Alliance for Progress included military aircraft, arms, and the creation of a psychological warfare division within the Colombian military, and would lay the groundwork for future securitization agreements like Plan Colombia, the Mérida Initiative and many others since deployed across Latin America, en route to American hegemony throughout the Western Hemisphere and an endemic problem of population displacement and migratory flows towards the empire’s core.

—

As Aerovías Panama Airways’ DC-7 taxiing down the runway at Tocumen International Airport in Panama, the atmosphere was raucous inside the airplane cabin. Miami’s Chief of Police, the State Attorney for Dade County and four of Metro Dade’s eleven commissioners were glad to take a respite from their daily responsibilities for a tax-payer-funded, all-expense paid trip to an exotic South American country. They were joined by several other Metro officials, including judges and court personnel that made up Colombian Consul-General Lievano’s 12-man People-to-People delegation.

Two reporters from the Miami Herald and Diario Las Américas completed the party of fifteen that had departed from Miami International airport earlier that Friday. After the short layover in Panama, the men arrived in Bogotá later that afternoon and checked into the Tequendama Hotel, centerpiece of a larger complex known as the Tequendama International Center, built by the American InterContinental Hotels Corporation through a partnership with the Colombian government.

Construction on the hotel began as La Violencia took hold of the countryside in the early 1950s and was inaugurated just before Gen. Rojas Pinilla ordered the mobilization of troops throughout the city and assumed power for the next six years. Colombia’s military dictatorship hardly put a damper on the burgeoning Latin American tourist industry, which had been born in the White House during a breakfast with Franklin Roosevelt and Pan American Airlines owner Juan Trippe, where the President asked the Pan Am executive to build 5,000 hotel rooms in Latin America as part of his Good Neighbor policy.

Using credits extended by the Export-Import Bank, Trippe established InterContinental as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Pan Am. President Truman continued the government subsidy of the hospitality concern with $12 million for the Tequendama project alone. Pan Am had a virtual monopoly of the air travel industry in the Americas during the post war and together with its tax payer-funded hotels went on to dominate a good chunk of the broader tourism industry as well.

Official itinerary activities for the recent arrivals from Miami wouldn’t begin until Monday and Lievano’s group looked forward to a weekend of leisure and entertainment in the Andean city and its surroundings, like the underground cathedral of Zipaquirá, built 200 meters beneath the earth inside the largest rock salt mine in the world. In the meantime, the delegation followed their bellhops through the lobby, which was still teeming with guests of the 16th annual Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) conference.

Earlier that morning, members had gathered to discuss the final report of IAPA’s ‘Freedom of the Press’ Committee, which had been convened for the single purpose of declaring Fidel Castro of being a threat to the free press and of organizing a campaign against IAPA itself, with the support of “all the communist parties of the Western Hemisphere”, according to the Chicago Tribune’s Jules Dubois, president of the Committee. Manuel Antonio “Tony” De Varona introduced Dubois with a message sent from New York accusing the Committee president of being a secret service agent of the United States and warning IAPA members that supporting the condemnation of the Cuban press would show them to be nothing more than “lackeys and puppets of the American government”.

Varona, former Prime Minister of Cuba, had been working with the CIA since 1958, when he was first recruited to lead a possible coup against Batista as the agency began to weigh its options in view of the dictator’s weakening grip on the island. Since Castro’s victory, the CIA moved Varona into a different role as the head of the Frente Revolucionario Democrático (FRD), an anti-Castro group comprised of the same men who would soon command the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion as part of the CIA-sponsored Brigada 2506.

Following a performative display of defiance by Dubois, who threatened the author of the blistering missive with a libel action, the fourth session of IAPA’s annual event moved forward with its agenda to declare Fidel Castro’s Cuba as an enemy of the “free press”. Jorge Zayas, editor in exile (Miami) of the Havana daily Avance, took the podium to parlay Dubois’ condemnation into a hemispheric fight against Soviet aggression and called for the “peoples of our America” to not “run from our responsibility in the Cold War”.

After a litany of grievances against the Castro government by half a dozen Latin American news publishers, the session ended with a word from Joshua B. Powers, who ran a CIA propaganda outfit called Editors Press Service. Powers announced a $4,000 infusion by top IAPA members to fund the activities of the newly-created Committee for Promotion. Ostensibly earmarked for the printing of pamphlets and brochures, the money would help cover the endemic shortfall in the Association’s finances.

IAPA was little more than an arm of American propaganda, and only one tentacle of a vast, global propaganda network operated by the CIA through people like Powers and James S. Copley, owner of the CIA-cutout Copley News Service (CNS), whose San Diego-based ‘news’ agency had been formed at the behest of President Eisenhower during a 1953 meeting with Copley and former OSS officer, Bob Richards, for the purposes of “supplementing CIA activity”, according to a story first broken by Penthouse magazine in 1977.

CNS had at least 23 spies-slash-journalists on the payroll, who worked with the CIA and FBI to plant stories and farm intelligence. CNS also ran two publications in California, which extended its counter-intelligence mission to social movements in the United States, such as black civil rights groups and anti-war protesters. Penthouse’s year-long investigation revealed how far the CIA’s tentacles reached into other publications in Latin America, of which Jim Copley had a bird’s eye view from his seat on IAPA’s board of directors.

Sitting on the board with Copley were representatives of some of the most important media companies and publications in the entire hemisphere. Individuals like Rómulo O’Farril Jr., proprietor of Mexican daily Novedades and part-owner of Telesistema Mexicano (later Televisa), the largest radio and television property in Latin America, and Agustín Edwards, the wealthy owner of Chile’s El Mercurio, and one of the prime movers behind the scenes of Salvador Allende’s 1972 assassination in concert with the CIA. Both sat on IAPA’s executive committee, as well.

Chairing the committee was Col. John R. Reitemeyer, U.S. military intelligence and president of The Hartford Courant, who would also be in Chile just before Allende took power and whose own words corroborated Penthouse’s allegations of IAPA’s deep ties to the CIA. In a 1974 letter addressed to CIA deputy director Vernon Walters, Reitemeyer railed against his (by then) former IAPA colleagues’ request to reveal “the names of newspapers or others who are alleged to have received subsidies of some kind from the CIA”. Declassified in 2003, the dispatch shows Reitemeyer’s indignation at the thought of publishing “a list of newspapers or agencies in Chili (sic.), or elsewhere for that matter, who received aid of any kind from the CIA. In fact”, he continued, “I think the writings of former CIA agents and others goes far beyond what I consider to be permissible bounds”.

The conference had opened a few days earlier with President Lleras Camargo himself delivering the keynote speech. A former journalist and one-time president of IAPA, Lleras Camargo addressed the room-full of spies and propagandists with his usual grandiloquence, which offered little in the way of substance, but plenty of quotable material for the Western media grasping for anything to counter perceptions of American imperialism.

“To condemn [the press] as a business, or an aberration of the capitalist system,” he railed without a hint of irony, “is a campaign that our generation recognizes as the prologue to generalized oppression, the palliative artillery that precedes the assault and occupation of a free territory.” Despite the collective media muscle assembled at the Tequendama hotel that fall, history was about to take a turn that would require more than a few magazines, radio broadcasts and Op-Eds to parse in their favor.

—

Dulles’ initial plans for Operation Pluto called for no less than 600 able-bodied anti-Castro militants to be trained by the U.S. military somewhere in Central America for an amphibious invasion of Cuba to be aided by U.S. air cover. Ultimately, Retalhuleu, Guatemala was chosen as the staging ground for the operation, and soon became the most compromised mission in the annals of the national security state. It was the worst-kept secret in Miami and even Guatemalan radio was reporting on the CIA’s boot camps in Retalhuleu. Cuban press denounced the planned invasion weeks before the CIA director and his Deputy, Richard M. Bissell, formally briefed the newly-sworn-in president on the matter.

Almost a year to the day CIA mercenary pilots shelled the city of Havana with four 100 lb. bombs, President John F. Kennedy was formally briefed on the plan to invade Cuba by the CIA director and his Deputy, Richard M. Bissell. After exhorting America’s adversaries to embark on a “new quest for peace” in his inaugural speech, Kennedy green-lit a plot to assassinate Fidel Castro with poisoned cigars, and the acts of sabotage on the island continued to ramp up.

By April, 1961, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had approved the CIA’s final attack plans and the anti-Castro paramilitary force trained in Guatemala, a.k.a. Brigade 2056, was ready for action. Only days before the all-clear was given, Havana’s biggest department store was destroyed in a blaze after CIA operatives had stuffed dolls with dynamite and blew up its stock warehouse, killing at least two people in only one of several fires and explosions that rocked the Cuban capital in the days leading up to the doomed mission.

On April 17th, 1961, a press release ostensibly issued by the putative leader of Cuba’s quasi-provisional government in Miami, José Miró Cardona, declared that the liberation had begun. The letter, which had in fact been written by CIA officer E. Howard Hunt Jr., marked the official start of the invasion, and every newspaper in America carried the story on the front page. Almost all of the publications also included a very clear disclaimer from the White House insisting that the United States was not involved, but was nonetheless rooting for the exiles.

Some accounts contend that Kennedy was not told until the operation was underway, which led to his decision to prioritize America’s plausible deniability and deny air cover to the CIA-trained rebels. In any case, he the invasion turned out to be a spectacular failure as result, with Castro making quick work of the Brigade 2056. Both the Pentagon and the CIA blamed Kennedy, eliciting desperate attempts to erase the pathetic results with another covert offensive.

Alfredo Izaguirre de la Riva, scion of Cuba’s oligarchy and high-level CIA asset was brought to Washington for top secret discussions. Prompted by Pentagon officials, Izaguirre related how the counter-revolutionary movement in Cuba was divided and morale was low, when it was suggested that a false flag attack on Guantanamo Naval Base would create a good pretext for direct invasion by U.S. marines. Later that night, Izaguirre met with his CIA handler, Frank Bender, and committed to the idea.

Upon his return to Cuba, Izaguirre set out to galvanize the counter-revolutionaries with promises of U.S. backing. A new coordinating group was formed to bring all the splinter movements together under one chain of command, and preparations for Operation Patty began. Slated for 10:00 am on July 26, the anniversary of the Cuban Revolution’s assault on Moncada, synchronized attacks were planned in Havana and Santiago de Cuba, where they intended to kill the Castro brothers, Fidel and Raúl, bomb an oil refinery, and launch mortars into Guantanamo Naval Base from a nearby farm to produce the pre-planned response by U.S. forces.

Four days before Patty was to go live, Cuban State Security forces detained the principle plotters and completely dismantled the operation. However, the CIA had a backup plan. Operation Liborio was activated later that summer, with the goal of unleashing mayhem in Havana by setting fire to major department stores and public utilities in order to rile up the citizenry, and take Fidel out during a public demonstration. Once again, the plot fizzled.

Two more assassination attempts against Castro were snuffed out in September and October, respectively. But finally, in November, the bottom fell out of the American intelligence community, and president Kennedy replaced Allen Dulles with John McCone as head of the CIA, who in turn fired most of the erstwhile director’s staff, and relieved many of his deputies. Thus remade, the agency would form part of yet another, even grander conspiracy to oust the Cuban leader. An ad-hoc interagency effort comprised of the CIA, the Pentagon, Justice and State Departments called Operation Mongoose.

Divided into six phases, Mongoose would deploy thousands of agents and infiltrators in pursuit of the elusive target. Also known as The Cuba Project, the new plan would begin with an “action” phase, moving the first assets into place in Cuba, followed by the “build up” phase. By August 1st, 1962, a policy check would be carried out before moving into the “resistance” or guerrilla operations phase, which would ostensibly result in the open “revolt”, and ultimately the toppling of the Castro regime, with the help of the U.S. military, if necessary.

Exactly one year after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, 83 U.S. warships, 300 fighter jets and 40,000 troops began military maneuvers on the east coast of the United States, while the CIA reacquainted itself with the mob to plan for yet another hit on Fidel Castro. From South Florida, the agency sent off several teams to begin training counter-revolutionary assets inside Cuba, and organizing a new communication system with the CIA’s largest outpost, the infamous “JM/WAVE” located inside the University of Miami.

Psychological warfare operations would also kick into high gear, with at least ten anti-Castro radio stations broadcasting subversive programming into the island several hours a day. Beaming out from United Fruit’s CIA-operated transmission tower off the coast of Honduras, the radio shows were only one part of Mongoose’s psyop arsenal, which also included magazines and motion pictures, all intended to demoralize he Cuban people and malign its leadership.

October 1962, had been marked on the special group’s calendar as the month when phases five and six of the Cuba Project would be completed, culminating in the establishment of a new government. But in September, a Mongoose asset caught wind of Soviet arms shipments to the island, and after Washington deployed U-2 spy planes to confirm the rumors, it was too late.

—

Castro had kept the Soviet Union’s overtures at bay for the most part, believing in the intrinsic merits of the Cuban Revolution as a sovereign struggle separate and distinct from any other. But, the unrelenting assaults from the United States left the regime no choice other than to accept the lifeline Nikita Khrushchev was extending. At first, the Soviets limited their help to shoring up the holes blown through the Cuban economy by the U.S., such as buying up the 700,000 ton sugar quota that Eisenhower had suspended. Inevitably, the relationship became closer, and soon arms and other war materiel was included in the aid packages coming from the Soviet Union.

Castro and Khrushchev met in July, 1962, just as phase 2 of operation Mongoose was in full swing, infiltrating CIA assets all over the country, and building the logistical support for the overthrow of the Cuban government. The Soviet premiere offered to place medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba to deter further U.S. aggression, and the Cuban leader immediately set out to begin construction of the sites to house them.

The Cuba Project came to a screeching halt when news of the Soviet missiles reached the White House, proving the effectiveness of the strategy. And instead of the U.S. puppet regime getting installed in Havana’s presidential palace projected in phase 6 of the special group’s best laid plans, the world was on the verge of a nuclear apocalypse, as the Kennedy administration wrestled with the sobering consequences of their reckless interventionism.

There has never been a more critical time to support independent media

RDMPRESS relies on your support to produce independent journalistic content. Please consider making a donation today.

After two weeks of brinksmanship between the superpowers, Khrushchev accepted the U.S. proposal to remove all missiles and strategic weapons on the condition that no further acts of aggression be carried out against Cuba. Unsurprisingly, America broke its word less than a week after it was confirmed that the Soviet missiles were being removed, and operation Mongoose was reactivated. But once again, Cuban security forces were able to frustrate the CIA’s men trying to commit major acts of sabotage at U.S.-owned copper and nickel mines in the eastern part of the island. The plot to blow them up was led by a former Batista officer, who landed in Cuba with eleven other CIA-trained exiles from Miami, even as U.S. and Soviet officials were negotiating the final terms of the deal at the United Nations.

Finally, Kennedy decided to end the naval blockade set around Cuba a month earlier and the Cuban Missile Crisis was officially over. On Christmas Eve, 1962, Castro released 1,189 captured Cuban mercenaries from the Bay of Pigs operation in exchange for $54 million in medical supplies and food. A crowd of 40,000 Cuban exiles received them at the Orange Bowl in Miami, where president Kennedy and his wife paid tribute to the ‘martyrs’ of the CIA. Less than a year later, Kennedy would become one himself. Shot down in broad daylight, his assassination continues to be the subject of much controversy and speculation. It’s not uncommon to find the names of Cuban exiles trained by the CIA in the plethora of files since declassified pertaining to that fateful day in Dallas.

—

The abiding prospect of nuclear annihilation during the Cuban Missile Crisis in the fall of 1962 crystalized the ongoing conflict between the United States and Cuba, creating a protected class of immigrants that vouched for U.S. interventionism around the world, and in some cases, actively participated in it. From 1960 to 1971, more than 600,000 Cubans would make the trip across the Florida straits, as the economic embargo imposed by Eisenhower and every U.S. president since, made life on the island impossible for all but the most committed to the Revolution. Enticed by nearly $1 billion dollars in public assistance programs awaiting them stateside, not to mention the resources pulled by civil society organizations, church groups and private fundraising efforts, it’s no wonder many Cubans decided to make the move.

Dubbed the “golden exiles” for the largesse extended to this first wave of Cuban immigrants, an important number were professionals, like doctors and engineers, representing a significant brain drain on Cuba. However, their degrees were not often recognized in the United States forcing them into other lines of work. Luckily, the CIA and the broader security interests of the United States would require many front companies and propaganda outlets to service their new focus on counterinsurgency operations in Central and South America, that came to dominate U.S. foreign policy over the following decades.

Following the fruitless adventures in Cuba, the CIA found it had developed a secret army of essentially stateless, rabidly anti-Communist mercenaries it could use in other undercover operations around the world at the height of the Cold War. Notorious figures like Ricardo “Monkey” Morales, who claimed to have trained Lee Harvey Oswald, or Félix I. Rodríguez, and Rafael “Chi Chi” Quintero, whose names would become household words during the Iran-Contra affair in the 1980s.

Since then, Miami has become a transfer terminal for empire; a kind of Grand Central Station at the edge of the Caribbean with multiple points of entry that connect to the many different parts of Latin America where its tentacles stretch, to overthrow governments, impose economic sanctions, shape policy and otherwise destabilize the periphery as George Kennan, the father of post-war U.S. foreign policy, prescribed to safeguard America’s wealth from a “jealous and embittered world”.

Cover Photo: Miami, Florida, 2019 – Federal security detail surveils crowd of protestors below from rooftop of a Florida International University (FIU) building during the 4th annual Hemispheric Security Conference. | Photo Credit – Raul Diego Medina for RDMPRESS. All Rights Reserved.